The SEIA Report Q4

Check Your Biases

By Sam Miller, CFA®, CFP®, CAIA®

Senior Investment Strategist

Why do some 401k plan participants invest equally across all the available plan options, regardless of their financial goals or comfort with risk?

Why do so many investors panic and sell after the market has already dropped 20%?

Why do employees often hold large concentrated allocations in their own employer’s stock, even when they know that they’re increasing their overall investment risk by doing so?

Why do people tend to buy stock in a company whose products they like and use, regardless of whether or not the company’s fundamentals are strong?

The answer to these and countless other investment “head-scratcher” questions relates to our human emotions and the cognitive biases that affect all of us. These biases not only impair our ability to remain emotionally disconnected from our money, they have the potential to derail even the most carefully constructed investment portfolios and financial plans.

One very tangible emotion felt by many investors, particularly when markets are declining, is stress. John Coates, a former trader turned neurologist, studied the effect of persistent exposure to stress on investment decision-making ability.1 He tested the cortisol levels of professional traders and found that it took a mere eight days of elevated market volatility to cause cortisol levels to skyrocket by 68%. What exactly was the impact of that rise? It led to a remarkable 44% decline in the trader’s appetite for risk. Coates was eventually able to calculate that individuals lose roughly 13% of their cognitive capacity when placed under stress.

With markets at or near all-time highs, and the current economic cycle eclipsing the longest in U.S. history, stress and cognitive biases have the potential to be more damaging than ever – causing even the most seasoned investors to trade at the wrong time for the wrong reasons. So, let’s take a closer look at some of the most common of these cognitive biases, and how investors can overcome them to achieve better outcomes:

1. Familiarity bias

Studies show that investors tend to prefer stocks in companies that they buy products from, work for, have a family connection to, or which are located near their home. Because of this familiarity bias, investors often perceive that an investment is less risky than it actually may be. The most evident and widespread example of this is home bias.

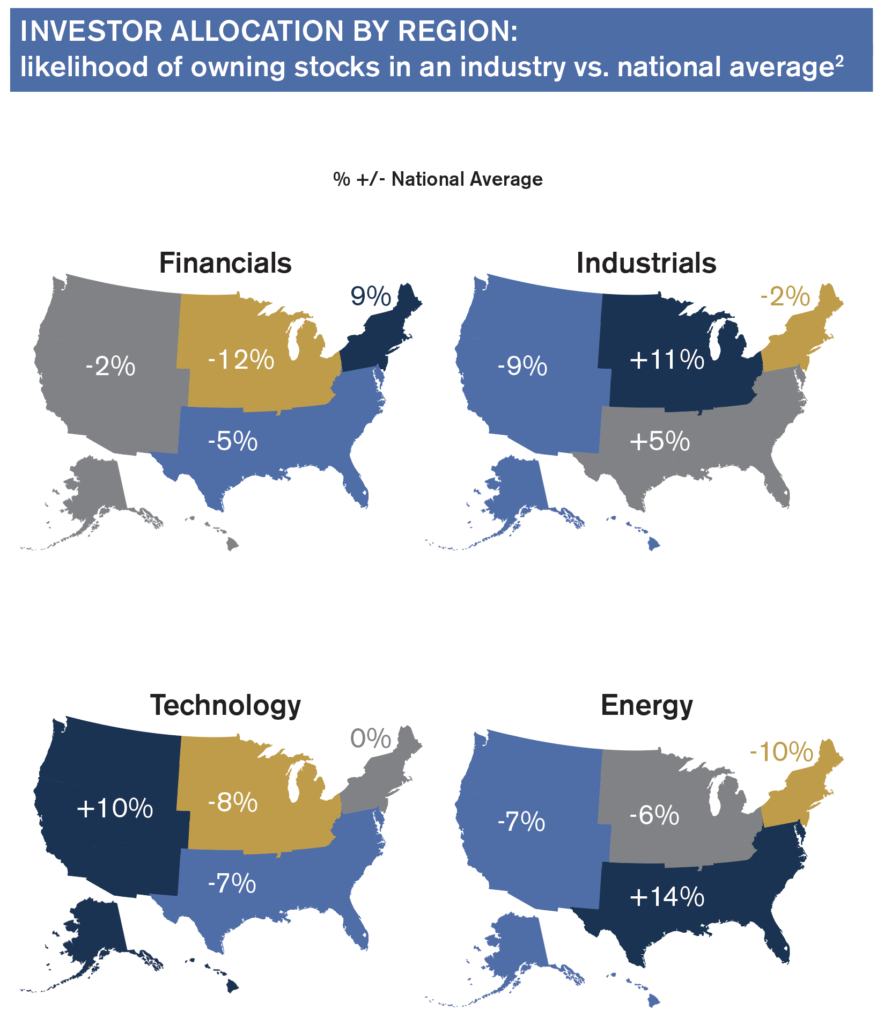

While the U.S. boasts one of the largest economies in the world, it still only accounts for less than one-fifth of global GDP. Yet, many U.S. investors hold a disproportionate amount of assets in domestic equities. Beyond that, home bias is also evident regionally. For example, investors in the northeast U.S. tend to have a greater allocation to Financial companies in their portfolios; likely a result of their proximity and familiarity with financial institutions based in New York and Boston.

How to combat: Stick to a more structured, disciplined investment strategy to help minimize the impact of subjective influences such as home bias and familiarity bias.

2. Confirmation bias

As individuals, we tend to seek out information that conforms to our current beliefs. Whether it’s subscribing to particular news feeds or surrounding ourselves with like-minded social media friends, it’s easier than ever to slip into an echo chamber of uniform thoughts, beliefs and information that supports our current opinion. People love to be told what they already “know,” and get uncomfortable when you tell them something new. It’s simply human nature to prefer having our existing beliefs confirmed rather than having to question why one might be wrong.

How to combat: Always challenge your prior conclusions. Seek out contrary opinions. And make a concerted effort to consider both sides of every debate equally.

3. Loss aversion

For most of us, the fear of experiencing a loss far outweighs the pleasure associated with experiencing a similar gain. Nobel Laureate, Richard Thaler, found that we feel the pain of a loss twice as much as we feel the joy from an equal-sized gain. The result is that we tend to avoid risk when and where possible. It’s a phenomenon that the media is all too aware of – intentionally leading with scary or sensational stories to grab your attention by exploiting this bias.

How to combat: While information is more readily available than ever, the sheer quantity doesn’t necessarily make it useful. In fact, parsing through the noise may be harder than ever. Employ a healthy skepticism when consuming media and seek out contrarian perspectives. You just may find that less is more when it comes to information.

4. Hot hand fallacy

This refers to the notion that a string of recent successes will likely be followed by more success. Certainly, the concept of momentum does exist in the investing world. But once an individual investor begins to think they have a hot hand, other behavioral biases like overconfidence and recency bias tend to creep in and lead to suboptimal outcomes.

Case in point: since the 2008 financial crisis, U.S. Growth stocks have had the metaphorical ‘hot hand’, consistently outperforming International and Value stocks by a wide margin. This has caused some investors to throw in the towel entirely on International and Value. Prudent investors, however, know that certain geographies and styles can experience long periods of relative underperformance, only to quickly and spectacularly take the lead when the tide turns.

How to combat: Try to separate skill from luck when assessing performance by looking at longer-term metrics. When determining expectations for future performance, review asset classes and investment styles over decades, not quarters or years.

5. Sunk cost fallacy

Have you ever invested more into a stock that has fallen, convincing yourself that by buying additional shares you’ll be able to recoup your earlier losses? Welcome to sunken cost fallacy. Simply put, the more you invest in something, the harder it psychologically becomes to abandon it.

How to combat: Strive to keep the big picture and your total portfolio (not just one position) in mind whenever making investment decisions. Often, it’s best to just cut your losses and move on.

6. Overconfidence

Ask a room full of people, how many of them think they’re a better than average driver. Though a statistical impossibility, undoubtedly far more than half of the audience will raise their hands. We naturally tend to be overconfident, and are prone to revising our beliefs only when it suits us.

In fact, studies have demonstrated that most investors consistently overestimate both the future and past performance of their investments. Looking solely at investors who believed they had outperformed the market, research shows that fully one-third of those individuals actually lagged by at least 5%, and another quarter lagged by more than 15%!3 Our overconfidence creates an alternative reality to protect us from feeling bad. However, this tendency often leads to investors holding undiversified portfolios and taking excessive risks.

How to combat: Emphasize process, guidelines, and rules when structuring your financial plan and investment policy. Those rules will help you systematically buy and sell, even when it may not feel good. And discuss with your advisor what actions you’ll take when the next market correction comes along. By identifying responses, before a stressful event happens, you may feel a greater sense of control when one actually occurs.

7. Status quo bias

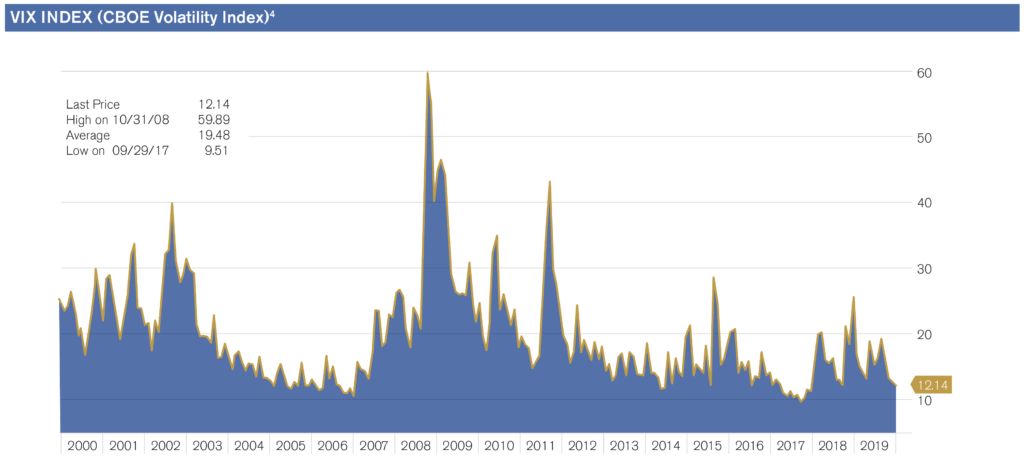

Humans are inherently creatures of habit who are averse to change. We prefer the current state of affairs. It’s the reason many portfolios end up with hundreds of holdings over time, also known as the endowment effect. But these sentimental attachments to a stock or portfolio can be problematic when it introduces undue investment risk or results in a suboptimal asset allocation. A long, drawn out economic cycle with relatively low volatility (like the one we’re currently experiencing) can lull investors into a false sense of complacency.

How to combat: Sit down with your advisor, take out a blank sheet of paper and sketch out what your ideal portfolio would look like (based on your goals, risk tolerance, and preferences) if you were starting from scratch. If that portfolio measurably differs from your current portfolio, there’s a chance your current portfolio may be suboptimal. Keep in mind that volatility can return without warning, so now’s the time to have your portfolio and financial plan stress-tested and ready for whatever the future may hold.

Just as with an addiction, the first step to overcoming emotions and cognitive biases is to acknowledge the impact they have on your financial decision-making. But acknowledging them isn’t enough. You also need to commit to taking proactive steps to avoid them. It starts by working with your financial advisor to develop a well thought out financial plan and an investment policy statement that defines your ability and willingness to take on risk and acknowledges the history of financial market returns and the inevitability of bear markets.

The best advisors don’t distinguish themselves with hot tips or following the latest investment trends; they maintain frequent, ongoing contact with you to help keep you on track toward your ultimate objectives.

Third Party Site

The information being provided is strictly as a courtesy. When you link to any of the websites provided here, you are leaving this website. We make no representation as to the completeness or accuracy of information provided at these websites. Nor is the company liable for any direct or indirect technical or system issues or any consequences arising out of your access to or your use of third-party technologies, websites, information and programs made available through this website. When you access one of these websites, you are leaving our web site and assume total responsibility and risk for your use of the websites you are linking to.

Dated Material

Dated material presented here is available for historical and archival purposes only and does not represent the current market environment. Dated material should not be used to make investment decisions or be construed directly or indirectly, as an offer to buy or sell any securities mentioned. Past performance cannot guarantee future results.